|

Bagworms and borers. Mites and moths. Lawn care operators have a lot to worry about when it comes to turf, but the threats don’t stop there. There’s an army of insects waiting to infest some of the key trees and shrubs on your client’s property.

Control: Prune out or hand-remove nests that can be reached. Use a long pole to dislodge tent caterpillar nests, or blast them out with a water hose. Don’t try to burn them out – no matter how cool it might look, Potter says. Reduced-risk caterpillar insecticides include spinosad , indoxacarb, chlroantraniliprole, or Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt). Pyrethroid sprays, or injecting trees with abamectin are highly effective, but nicotinoids are not very active against caterpillars, Potter says.

Control: Handpick the bags off branches, especially in late fall, winter, and early spring. If spraying, target bagworms when they are newly-hatched and small – in late May or June. See insecticide suggestions for web-making caterpillars.

Control: Spray egg masses with horticultural oil or scrape them off and destroy. Insecticide-treated or sticky tree bands intercept some larvae crawling up the trunks. Do not apply stickum directly to the bark, Potter says. See insecticide suggestions for web-making caterpillars.

Control: Prune out clusters of larvae or hand pick them. Spinosad, pyrethroids and neem-based products will control sawflies. Smaller larvae are susceptible to insecticidal soap, but Bt is not effective against sawflies, Potter says.

Control: Soil-applied systemic nicotinoid insecticides applied in early spring are effective as a preventive treatment. 5. Spider mites Control: They’re not susceptible to most insecticides – in fact, treatments with nicotinoids may increase their egg production. Use a registered miticide instead. 4. Japanese beetles Control: Traps attract more beetles than are caught and may make matters worse. Chlorantraniliprole (non-toxic to bees) or pyrethroids will do the trick. Carbaryl works, but is hazardous to bees and may increase mite problems, too. 3. Scale insects Control: If spraying, monitor for crawler hatch. You can time it with the bloom dates of certain plants. Your county agent may have a specific calendar. Residual sprays with pyrethroids will intercept crawlers before they settle; horticultural oil or insecticidal soaps will control active or newly-settled crawlers hit by the spray. Research by one of Potter’s students showed that excluding ants with a banded trunk spray or sticky band can significantly reduce soft scale infestations by preventing tending, allowing natural enemies like lacewings to gobble up the scales.

Control: Plant well-adapted species and cultivars and minimize tree stress. Avoid trunk wounds, which attract the egg-laying female. Preventive bark sprays with pyrethroids and anthranilic diamides work well for clearwing borers; pyrethoid bark sprays or systemic nicotinoids work on flat-headed borers, Potter says.

Control: Contact your county agent or state extension entomology specialist for status of EAB in your area. Emamectin benzoate treatments – either via basal drench or injection/infusion – have shown to be effective for up to three years. Systemic nicotinoids also can be used. The author is editor of Lawn & Landscape. Send him an e-mail at cbowen@gie.net. |

Explore the January 2011 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Lawn & Landscape

- Bartlett Tree Experts adds Lee Gilman & Associates

- Stay Green acquires JH O'Brien in California

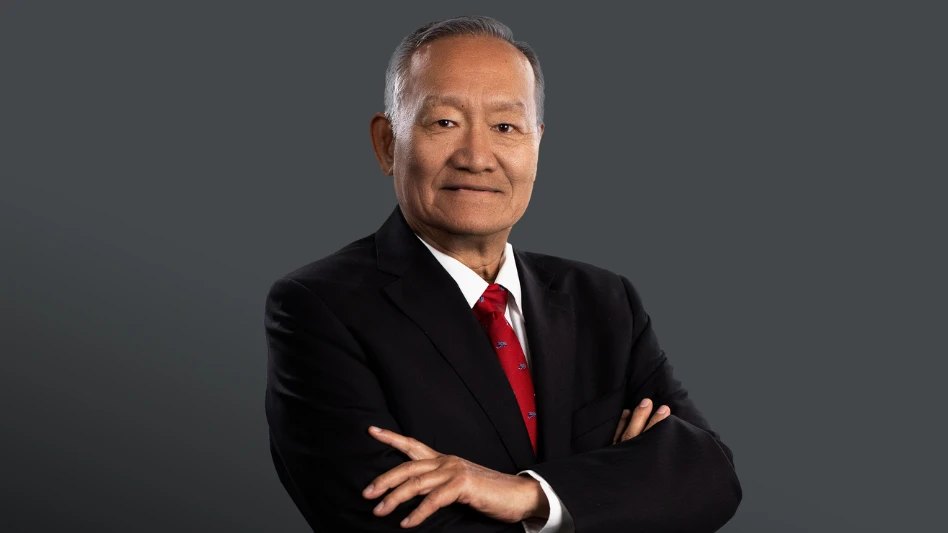

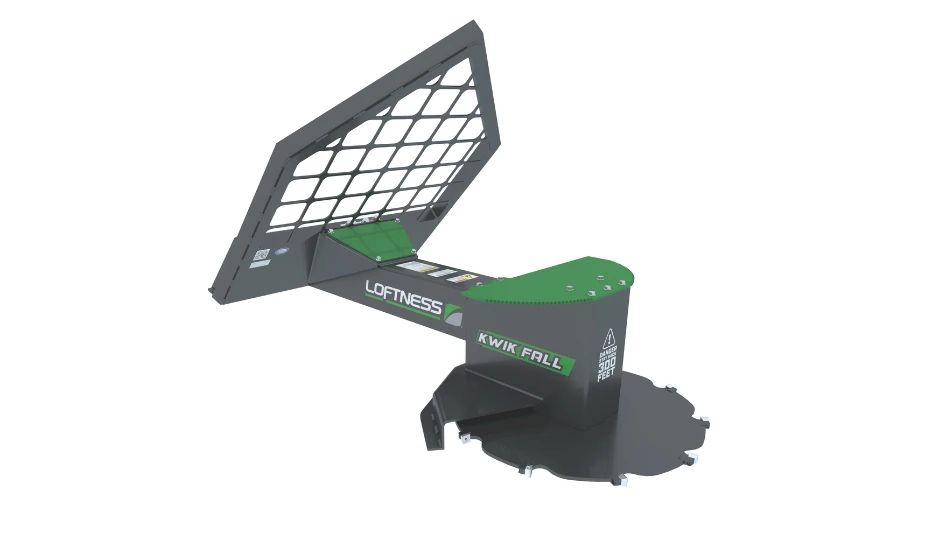

- Loftness names McComas as chief operating officer

- Wilson360 names Anderson as featured speaker for Thought Leaders Retreat 2026

- Kubota introduces SVL110-3 compact track loader

- Hittle Landscaping acquires Wesley's Landscape & Lawncare

- Aquatrols Company's Precip Acres

- JCB debuts 250T compact track loader, 25Z mini excavator at ARA Show

The Eastern tent caterpillar is the first one to show up, usually in March or April. It makes a compact silk nest in a branch crotch and defoliates wild and ornamental cherries, crabapples, and related trees. Fall webworm makes a loose nest over the whole end of a branch from mid-summer to fall.

The Eastern tent caterpillar is the first one to show up, usually in March or April. It makes a compact silk nest in a branch crotch and defoliates wild and ornamental cherries, crabapples, and related trees. Fall webworm makes a loose nest over the whole end of a branch from mid-summer to fall.  Bagworms resemble pine cones and typically, clients don’t recognize them as an insect problem until the damage is done. “Evergreens don’t recover well from defoliation,” Potter says. Females lay eggs inside the bag in autumn and the egg masses overwinter in the old bags on the tree until hatching the following spring. The male is a furry moth.

Bagworms resemble pine cones and typically, clients don’t recognize them as an insect problem until the damage is done. “Evergreens don’t recover well from defoliation,” Potter says. Females lay eggs inside the bag in autumn and the egg masses overwinter in the old bags on the tree until hatching the following spring. The male is a furry moth. These exotic pests were brought over by an ill-guided if industrious person in the 1860s to jumpstart a U.S. silk industry. (It didn’t work; they got loose and now they’re a big problem.)

These exotic pests were brought over by an ill-guided if industrious person in the 1860s to jumpstart a U.S. silk industry. (It didn’t work; they got loose and now they’re a big problem.) You’ll always find sawfly larvae clustered on evergreens, where they chew branches to nubs. Their winter pupal cases look like beans, and you can tell them apart from a caterpillar because they have six or more pairs of fleshy bumps on the abdomen (caterpillars have 2-5 pairs). “They won’t leave much of a Mugo pine behind when you have an outbreak,” Potter says.

You’ll always find sawfly larvae clustered on evergreens, where they chew branches to nubs. Their winter pupal cases look like beans, and you can tell them apart from a caterpillar because they have six or more pairs of fleshy bumps on the abdomen (caterpillars have 2-5 pairs). “They won’t leave much of a Mugo pine behind when you have an outbreak,” Potter says. Boxwood leafminers hollow out leaves like pita bread, and boxwood psyllids suck the juices from new growth causing rosettes of cupped leaves. The damage is done in early spring, and hard to fix by the time it is visible.

Boxwood leafminers hollow out leaves like pita bread, and boxwood psyllids suck the juices from new growth causing rosettes of cupped leaves. The damage is done in early spring, and hard to fix by the time it is visible. These “nasty little creatures,” as Potter refers to them, are more closely related to spiders than true insects. They drain individual plant cells of their chlorophyll with needle-like mouthparts, which renders leaves stippled and off-color. To find them, beat foliage over a sheet of paper on a clipboard; they’ll be about the size of the period at the end of this sentence. They like burning bush, roses, Freeman maples, spruce, boxwood and other species.

These “nasty little creatures,” as Potter refers to them, are more closely related to spiders than true insects. They drain individual plant cells of their chlorophyll with needle-like mouthparts, which renders leaves stippled and off-color. To find them, beat foliage over a sheet of paper on a clipboard; they’ll be about the size of the period at the end of this sentence. They like burning bush, roses, Freeman maples, spruce, boxwood and other species. These are Potter’s favorite insect, and they eat nearly everything they come into contact with – 300 plants on the menu – “skeletonizing” leaves. But they’ll starve before they’ll eat red maples, dogwoods or tuliptrees, Potter says. The beetles are the adult version of grubs, and are worst in the summer – June through mid-August.

These are Potter’s favorite insect, and they eat nearly everything they come into contact with – 300 plants on the menu – “skeletonizing” leaves. But they’ll starve before they’ll eat red maples, dogwoods or tuliptrees, Potter says. The beetles are the adult version of grubs, and are worst in the summer – June through mid-August. Armored and soft scales encrust branches and bark of plants, sucking juices and causing crawn thinning and dieback. Soft scales produce copious honeydew, essentially “sugary diarrhea” that coats leaves and bark, attracts wasps and promotes growth of black sooty mold, Potter says. Ants often tend soft scales for their secretions – it will taste like maple syrup.

Armored and soft scales encrust branches and bark of plants, sucking juices and causing crawn thinning and dieback. Soft scales produce copious honeydew, essentially “sugary diarrhea” that coats leaves and bark, attracts wasps and promotes growth of black sooty mold, Potter says. Ants often tend soft scales for their secretions – it will taste like maple syrup. These insects are especially bad in transplants or stressed trees. There are two types: clearwing borers (adults are wasp-like moths) that push sawdust out of bark, and flat-headed borers (adults are beetles) that leave a D-shaped hole in trees. Females lay eggs on bark or under bark flaps. Symptoms include thin crowns and dieback, and girdling in the branches.

These insects are especially bad in transplants or stressed trees. There are two types: clearwing borers (adults are wasp-like moths) that push sawdust out of bark, and flat-headed borers (adults are beetles) that leave a D-shaped hole in trees. Females lay eggs on bark or under bark flaps. Symptoms include thin crowns and dieback, and girdling in the branches. “If you don’t have it, you’re going to get it. It’s a nightmare,” Potter says. If landscape trees are not protected, you can “kiss your ash goodbye.”

“If you don’t have it, you’re going to get it. It’s a nightmare,” Potter says. If landscape trees are not protected, you can “kiss your ash goodbye.”